Keith’s Letter

On September 26, 2001, I worked the 3-11 shift in the ER at OSF. I had elderly patients as usual and several signed out and went home when they realized how long they were going to wait for a bed in the hospital. They were sick, and I intended to admit them, but they just couldn’t take lying on a stretcher for many hours and so politely told me that they “needed to go home”.

The ER has an administrator on call every night to call at home if there are problems an attending physician in the ER would want to discuss. These calls usually did not help at the time the call was made.

On September 27, 2001 I decided that Keith Steffen, CEO at OSF-SFMC, should at least know of my concerns and wrote him a letter and copied it to all of my colleagues in the ER and to other OSF administrators. (See letter below.) Someone warned me that I might get fired if I sent the letter. I knew that to be true, but thought it needed to be done.

I did not hear back from Keith but did hear the next day from Dr. George Hevesy who had been promoted to ER director on August 1 to replace Dr. Rick Miller. His secretary handed me his letter to me as I was starting to resuscitate a man in the ER who had a cardiac arrest and was brought in by ambulance.

George’s letter put me on probabation for 6 months. It also stated that starting in November, I would only work in OSF Prompt Care. Hevesy did not disagree with the content of my letter but told me that I had gone around normal communication channels and that I would be suspended from the ED for 6 months. After I read the letter, I called George at OSF’s new Center for Health where he was working and asked him if he was really serious about what he had written. He said that he was and for me to stop in and see him sometime so we could talk.

-----------------------

September 27, 2001

Keith Steffen, Administrator

OSF Saint Francis Medical Center

Peoria, Illinois 61637

Dear Keith:

I started working at OSF-SFMC in 1971 as an orderly on 8B. Most of my last 30 years have been spent inside this building. OSF-SFMC means everything to me. Please interpret the following knowing my heart and spirit are with St. Francis and always will be.

I worked 3-11 last night in the main ER. The ER mayhem and disarray that usually exists was actually somewhat manageable. However, patient-waiting time from disposition to arrival on the floor was unbearable. Two sick patients of mine, rather than staying in the ER all night, politely decided to sign out, go home, and hope for the best.

Giving appropriate care in the ER can be challenging but having no room upstairs to admit the patient can be life threatening to the patient. Should I call other medical centers around the area/state for their admission and subsequent care before I see the patient or after? Studies have shown increasing time spent in the ER increases patient morbidity. Obviously, I don't want to do this. Please tell me what to do.

An ER crisis has been occurring for many years in our ER. But last night with "home diversion" of patients we have reached an all time low. This cannot continue.

I need an immediate answer from you today as to how I should approach these sick patients and their families. I will meet with you any time today or tonight.

My pager is always on (679-1980.)

Sincerely,

John A. Carroll, MD

cc: Sue Wozniak, Chief Operating Officer

Tim Miller, MD, Director of Medical Affairs

Susan Ehlers, Assistant Admimstrator Patient Care Delivery Systems

Paul Kramer, Executive Director of Children's Hospital of Illinois .

Lynn Gillespie, Assistant Administrator Organizational Development

Emergency Department Attendings

---------------------------------

On April 6, 2006 the Peoria Journal Star published the article below regarding the new Children's Hospital that will be built. Please note Mr. Steffen's comments regarding bed capacity problems and patient diversion at OSF. Was this institutional neglect by OSF attempting to stack to many patients inside the medical center? How many people suffered under this system? When I wrote him almost five years earlier, I was immediately placed on probation and then fired three months later. Will that be Mr. Steffen's fate as well?

What the Journal Star did not report was that Jackson Jean-Baptiste, a Haitian Hearts patient, was refused care at OSF and died several months ago. Many Haitian Hearts patients are now suffering and being denied care at OSF. This is contrary to what Catholic social teaching states and the Catholic Bishops Ethical and Religious Directives mandate.

Haitian Hearts obviously did not financially break OSF with the announcement of their new 200 million dollar building. It is truly a blessing for central Illinois children. However, Haitian children deserve the best available as well.

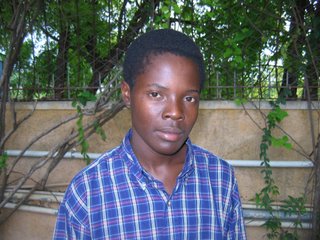

Until OSF can change its heart and return to the founding Sisters mission philosophy, they will have the technolgy but not the touch. The picture is of a Haitian baby where I work in Haiti. This hospital has no running water...a bit different than OSF-CHOI.

A medical milestone

Saint Francis expansion will alter Downtown landscape

Thursday, April 6, 2006

BY DAYNA R. BROWN

OF THE JOURNAL STAR

An eight-story, concrete and glass addition to OSF Saint Francis Medical

Center will permanently enhance Peoria's medical skyline - and the area's

economy. This new facility will be home to the Children's Hospital of Illinois and

is the largest building construction project in Peoria history.

"It's unusual for a community of this size to have its own children's

hospital," said pediatrician Dr. Rodney Lorenz, who also is interim dean at

Peoria's medical school. "We are blessed."

The new building will be located north of the hospital's main facility. It

will sit on the site of Medi-Park 1, which will be torn down when a new $33

million parking deck is completed later this year.

Construction is difficult on the site because it slopes 60 feet from top to

bottom. But it was the only area on the hospital's 33-acre campus where

there was enough room for this facility, administrators said. The

Children's Hospital wanted to stay on the Downtown campus because there is

$45 million in annual savings by sharing services with St. Francis.

The expansion is needed because the hospital is out of space,

administrators said.

St. Francis had to divert patients to other hospitals Wednesday, and it has

been that way much of the past month because there aren't enough beds, CEO

Keith Steffen said. Just last year, more than 200 patients had to be sent

to other locations.

But when the $234 million construction project is completed, that no longer

will be a problem, Steffen said.

"We've seen significant growth over the past few years," Steffen

said. "We'd be remise . . . if we didn't respond."

The new building will be 440,000 square feet, almost twice the size of the

hospital's Gerlach Building, which houses surgery, the emergency

department, most of medical imaging and five intensive care units.

It will allow for the consolidation of all of the Children's Hospital

services, which are currently located in six buildings, and provide all

pediatric patients private rooms.

"Right now it is hard for people to find the Children's Hospital because

it's buried in St. Francis," said Dr. Rick Pearl, surgeon-in-chief of

Children's Hospital. "I just run in circles, all day long."

The new facility, which will be physically attached to St. Francis but will

have its own entrance, will bring the hospitals staffed beds from 560 to

616. It will have three floors dedicated solely to children. Another three

floors will have shared services for adults and children, including surgery

rooms and the emergency department.

The decor will be "kid-friendly," with bright colors, play areas, music and

favorite children's characters, doctors said. And the rooms will provide

space for parents to stay with their child.

"I think it's very important for a child to feel comfortable," said Dr.

Ravindra Vegunta, director of pediatric minimally invasive surgery at

Children's Hospital. "The more happy the patient, the more cooperative a

patient and that will aid in recovery."

There will be one adult cardiac floor in the new building because more

space was needed for that department, administrators said.

Moving the pediatric services out of the current facility will free up

needed space for adult patients and other hospital needs, administrators

said.

The project also will include a "much needed" emergency department

expansion. The current emergency room was constructed to serve 32,000

patients annually, but this year it will surpass 62,000, Steffen said.

St. Francis is the largest hospital in downstate Illinois, employing

approximately 5,200 people, and the only Level 1 trauma center in the area.

In addition to 850 construction jobs, the project will create a need for

another 1,000 jobs related to health care.

Children's Hospital of Illinois was formed in January 1990, and draws from

a 30-county area. Annually, it admits about 5,000 children and treats

30,000 outpatients.

Areas hospitals - including Methodist Medical Center, Proctor Hospital and

Pekin Hospital - have given support for the project, Steffen said.

If the plans are approved by the state, which is required, construction

will begin in spring 2007, with a completion date of 2009. Hospital

officials plan to file for state approval by the end of the month, and said

they believe they will be approved.

"We are in the business of patient care," Steffen said. "This project

says . . . we are going to do it more efficiently, more effectively, more

conveniently."

Dayna R. Brown can be reached at 686-3194 or dbrown@pjstar.com.

----------------------------

The Journal Star then offered this editorial--

Monday, April 10, 2006

When Keith Steffen, OSF Saint Francis Medical Center CEO, got to work Wednesday morning, he was greeted with familiar news: the intensive care unit was full. Because of overcrowding, St. Francis annually diverts 200 patients to other hospitals, 100 of them children. That space crunch is precisely why Steffen would announce later in the day a $234 million expansion of St. Francis. The largest medical center in downstate Illinois isn't big enough.

The single biggest private building project in Peoria's history, if approved by state regulators, will shoehorn an eight-story building onto the Downtown campus and position St. Francis to meet the medical needs of central Illinois and beyond for the next 25 years. Once the so-called Milestone Project is done, St. Francis will have three new floors for the Children's Hospital of Illinois, three more for diagnostic services and surgery, one for adult cardiac patients and a new and bigger emergency room.

With the expansion, all of the hospital's 616 rooms - it has 560 now - will be private, which has health and customer satisfaction advantages. New surgery rooms will be large enough to accommodate robotics and other technology, some $47 million worth. A larger ER will no longer have to operate at twice capacity.

Simply put, the 440,000-square-foot addition - twice the size of the Gerlach Building that spans Glen Oak Avenue - will make St. Francis more competitive in a changing marketplace. Rural hospitals are referring more patients to Peoria than ever before. Some 35 percent of St. Francis' customers come from outside the Tri-County. One of the biggest growth areas is pediatric care, especially for high-risk infants.

OSF officials say the added efficiency will help keep a lid on inflation-shattering medical costs. The Children's Hospital, for example, is spread across six buildings. Now make that one. Administrative offices scattered across the city also will come under one roof after construction is completed in 2009.

This project benefits more than just St. Francis. First, it will create 850 construction jobs and up to 1,000 more permanent ones, including 300 more nurses and technicians. Second, it anchors Peoria's medical community Downtown for as far as the eye can see. When St. Francis built its Center for Health on Route 91 five years ago, there was a fear the hospital might eventually move north. No more. Between this project, OSF's $33 million parking deck now under construction and Peoria Surgical Group moving to the medical school campus, private medical investment Downtown will approach $300 million. What a boost for Renaissance Park.

This also will create a new front door for St. Francis off a rebuilt Interstate 74. Anything that makes it easier to navigate this labyrinth of a hospital is a plus. Finally, this expansion was endorsed by Methodist and Proctor hospitals. Hallelujah. Doesn't happen enough.

There will be naysayers. Indeed, it's a lot of money to add fewer than 50 patient rooms. Then there is the question of need. The Illinois Health Facilities Planning Board initially refused to approve the Center for Health on that basis. Ultimately jam-packed surgery rooms and full intensive care beds showed the flaws in that analysis. It's hard to imagine state regulators not looking favorably on this request.

----------------

My comments:

Finally, after many years, it was stated that the ER at OSF was operating at twice its capacity. Even Mr. Steffen stated that they would be "remiss" if changes weren't made. OSF has been "remiss" for many years now regarding excessive patients in the ER and inadequate bed capacity in the main house.

In the April, 2006 issue of Academic Emergency Medicine an article regarding overcrowding in the emergency department describes the problem very clearly. The journal reports, "The phenomenon of emergency department crowding has become recognized across the globe as a serious public health threat. ...experts widely agree that crowding in the emergency department (ED) is a system-wide problem, not one that results solely from problems in the ED or one that can be addressed using only ED based solutions. Crowding has become a shared burden for emergency providers. Each of us has a collection of stories to tell about how crowding has affected our patients, their families, our cowokers, and our own professional satisfaction."

----------------------------

June 16, 2006

Emergency System Called Very Ill

On June 15, 2006, USA TODAY had the above headline over an article on their front page.

The nation’s emergency medical system is in a dangerous state of crisis, says a new series of landmark reports. The Institute of Medicine recently released extensive reports which were prepared by a 40-member board after a two-year investigation. The IOM report states that the U.S. life saving system is failing.

The IOM reports detail how hundreds of thousands of lives are affected every year by EMS deficiencies that are not obvious. The chair of the panel, Gail Warden, stated that “in most communities, there is a crisis under the surface.”

Many emergency rooms barely can handle their daily patient loads, children don’t always get good care, and the quality of rescue services is erratic, the report says. A USA TODAY probe found a 10-fold difference between major cities in cardiac arrest survival rates.

Dr. Arthur Kellermann, director of the Center for Injury Control at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta stated that the problem with hospital bed capacity slows the emergency department admission of sick patients and more patients are diverted to other hospitals. In every minute of every day, an ambulance carrying a patient is turned away “diverted” when an emergency room says it is too full to take patients.

This sounds very much like OSF in Peoria. Throughout this website, I have questioned the monopoly of paramedic transport care in Peoria. The IOM report mentions, crowding and ambulance diversion also occur because of lack of coordination among emergency medical response teams and hospitals…as well as entrenched professional interests. With regards to Peoria, I would say the “entrenched professional interests” are centered around the medical centers and their relationship with Advanced Medical Transport.

There is a “crisis under the surface” in Peoria that will eventually become apparent.

-------------------

Emergency Medical News

October, 2008

In 2006 there were 119.2 million ED visits in the United States.

Dr. Arthur Kellerman agreed that it was easy to blame the problems of crowding on the uninsured. "It gives the decision-makers an excuse to ignore it or blame an unempowered segment of society. These aren't contributing to the growth of emergency department visits," he said. "We know the major problem in crowding is the boarding of patients."

Dr. Peter Viccellio commented on crowding in the ED: "...the problems and solutions are necessarily institutional, and cannot be addressed by focusing on the ED in isolation."

I believed in 2001 and still believe in 2008 that my letter to Mr. Steffen, other OSF administrators, and to my colleagues in the ER was was appropriate and that changes needed to be made to protect our ER patients.

-----------------------

February, 2009

Well, the financial crisis in the U.S that is putting many people out of home and job is also putting many of them in our overcrowded ER's. See

this post.

So in addition to OSF's greed, the dismal national economic picture in 2009 will imperil people's health all the more.

--------------------

October, 2009

Annals of Emergency Medicine, October, 2009

ED crowding affects care negatively.

Not only does it reduce access to emergency medical services, but also it is associated with delays in care for cardiac, and stroke patients, as well as those with pneumonia, and is associated with an increase in patient mortality. ED crowding has been associated with prolonged patient transport time, inadequate pain management, violence of angry patients against staff, increased costs of patient care, and decreased physician job satisfaction.

--------------

More about ED crowding...even in 2010. Why would Dr. Hevesy put me on probation in 2001 after I wrote Mr. Steffen about my concerns?

www.medscape.com

From American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Washington Watch: CDC Report on ED Capacity

Kathleen Ream

Posted: 02/05/2010

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released a report entitled Estimates of Emergency Department Capacity: United States, 2007. This report is based on data from the CDC's 2007 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS). Inaugurated in 1992, the NHAMCS is now the longest continuously running national survey of hospital ED use.

The report notes that over the last several decades, the role of the ED has expanded from primarily treating seriously ill and injured patients. The report recognizes that EDs now also provide urgent and unscheduled care to patients unable to access their providers in a timely fashion and provide primary care to Medicaid beneficiaries and uninsured patients. As a result, EDs are frequently overcrowded with the most common contributing factor being the inability to transfer ED patients to an inpatient bed once the decision is made to admit them. "As the ED begins to 'board' patients, the space, the staff, and the resources available to treat new patients are further reduced," the report states. It continues, "A consequence of overcrowded EDs is ambulance diversion, in which EDs close their doors to incoming ambulances. The resulting treatment delay can be catastrophic for the patient."

According to the CDC survey, approximately 500,000 ambulances are diverted annually in the United States. The survey also shows that large EDs serving more than 50,000 patients each year represent just 17.7% of all EDs in the nation, but account for 43.8% of all ED visits in 2007. The implication, according to the report, is that small EDs with annual visit volumes of less than 20,000 patients may not experience crowding.

Other data from the survey show that about one-half of all hospitals with EDs had a bed coordinator or "bed czar," 58% had elective surgeries scheduled five days a week, and 66% had bed census data available instantaneously. Electronic medical records (EMRs), either all electronic or part paper and part electronic, were used in 62% of EDs. Basic EMR systems containing patient demographics, problem lists, clinical notes, prescription orders, and laboratory and imaging results were reported in l5% of EDs. However, the CDC could not accurately determine the prevalence of fully functional EMRs that also include features such as electronic transfer of prescription orders, warnings of drug interactions or contraindications, and reminders for guideline-based interventions.

Additional survey data show:

Overall, 62.5% of EDs reported that they board admitted ED patients for more than two hours while waiting for an inpatient bed. Among EDs that board patients, 14.8% use inpatient hallways or other space outside of the ED when critically overloaded. A "full capacity protocol" that allows some admitted patients to move from the ED to inpatient corridors while awaiting a bed was used by 21.1% of EDs.

EDs with more than 20,000 annual visits comprised more than 70% of EDs in metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). When compared to EDs in rural areas, EDs in MSAs were more than twice as likely to board patients for more than two hours in the ED while waiting for an inpatient bed (77.4% versus 32.8%).

More than one-third of EDs had an observation or clinical decision unit. About a third of EDs used a separate fast track unit for non-urgent care.

In the previous two years, 24.3% of EDs increased their number of standard treatment spaces, and 19.5% expanded their physical space. Of those EDs that did not expand their physical space, 31.5% plan to do so within the next two years.

Zone nursing was employed in 35.3% of EDs. "Pool nurses" that can be pulled to the ED to respond to surges in demand were available in 33.2% of EDs.

Bedside registration was used in 66.1% of EDs, with 40% using computer-assisted triage. Electronic dashboards were utilized by 35.2% of EDs, and 9.8% used radio frequency identification tracking.

GAO Study Finds ED Crowding Continues

According to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report released June 1, hospital EDs continue to be overcrowded, with lack of access to inpatient beds continuing as the main contributing factor. The GAO first reported that most emergency departments experienced some degree of crowding in 2003 (Hospital Emergency Departments: Crowded Conditions Vary among Hospitals and Communities, GAO-03-460). The GAO was asked to revisit this issue in response to several studies that have associated crowded conditions in EDs with adverse effects on patient quality of care.

The GAO examined three indicators of ED crowding - ambulance diversion, wait times, and patient boarding - along with various factors that contribute to crowding. In doing so, the GAO reviewed national data, conducted a literature review of 197 articles, and interviewed individual subject-matter experts and officials from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and professional and research organizations.

National data showed that about one-fourth of hospitals reported going on ambulance diversion at least once in 2006. According to the GAO's analysis of 2006 data from the HHS's National Center for Health Statistics, average wait times continued to increase, with significant numbers of visits exceeding recommended wait times based on patient acuity levels, as summarized here:

Patients needing immediate care (recommended maximum wait to see a physician of less than one minute) waited an average of 28 minutes to be seen by a physician. 73.9% of these patients waited longer than the one-minute recommendation.

Patients with emergent conditions (recommended maximum wait of 14 minutes) waited an average of 37 minutes to see a physician. 50.4% of emergent patients waited longer than 14 minutes.

Patients with urgent complaints (recommended to be seen within 60 minutes) waited an average of 50 minutes, with 20.7% of patients waiting longer than 60 minutes.

Semi-urgent conditions (two-hour maximum wait recommended) had an average wait time of 68 minutes, with 13.3% of patients waiting longer than the maximum recommended timeframe.

Non-urgent patients (24-hour recommended timeframe) had an average wait time of 76 minutes, with no ED reporting wait times to see a physician in excess of 24 hours.

Although national data on patient boarding is limited, the articles reviewed by the GAO and the experts interviewed reported that the practice is a continuing problem due to the lack of access to inpatient beds. In turn, the lack of access to inpatient beds is due to the competition for available beds between hospital admissions from the ED and scheduled admissions, such as elective surgeries, that can be more profitable for the hospital.

While the GAO found that studies on solutions to ED crowding are also limited, strategies have been successfully implemented in isolated cases. One solution found in case studies conducted at several hospitals was to streamline elective surgery schedules, thereby increasing the opportunity for ED admissions. Regarding ambulance diversion, some local communities have established policies that make diversion the last resort for any hospital, as it often leads to critical cases not receiving the immediate care they need. Other strategies include the use of on-call physicians to determine the best ambulance destination for each patient or state policy prohibiting hospitals from going on diversion unless under inoperable conditions.

Strategies to decrease ED wait times included increasing the speed with which laboratory results are available, accelerating care during the triage process by eliminating some of the administrative work associated with patients entering the ED, and implementing a system allowing non-urgent patients to be seen by a medical provider other than a physician. However, none of the strategies to address crowding have been assessed on a state or national level.

The GAO found that there are several other frequently reported causes for ED crowding, including a lack of access to primary care; a shortage of available on-call specialists; and difficulties in transferring, admitting, or discharging psychiatric patients. Less commonly cited causes of ED crowding included an aging population, increasing acuity of patients, staff shortages, hospital processes, and financial factors.

For the full report, go to http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d09347.pdf.

-----------------

Hi Everyone!

It is June, 2010. Can you believe it?

Well, Emergency Department crowding is still an issue in 2010 just as it was in 2001.

Here is a

post from today.

We will stay in touch.

jc

June 26, 2010

-----------

Hi Everyone,

Well, it is May, 2011. Time flies when you are having a good time.

I posted

this article yesterday.

We will stay in touch and thanks for reading.

jc

-------

Hi Everyone,

Today is June 1, 2011.

I posted

this today.

Later,

jc

------

Hi Everyone,

Today is October 17, 2011.

I posted

this today.

Stay well.

John

-------

Dear Everyone,

It is December 23, 2011. It is very sunny and clear today. I still need to rake some leaves in the backyard.

Hope you are well.

I posted

this today.

Merry Christmas,

John

-----------

May 27, 2012

Dear Everyone,

It is Memorial Day Weekend. Hope you all are well.

I posted

this article yesterday. It is from Edmonton and mentions a doctor who notified administrators of his concerns of danger in the ED due to overcrowding in 2008. But his concerns were not addressed.

This sounds familiar to me.

Also, in Peoria, we now have two fire stations that are paramedic. And in the near future all new firefighters in Peoria will have to be paramedic. Please see

this post.

So times are changing for the better in Peoria. Change is hard when corruption is deep. And when our local medical leaders who have corrupted the system here for so long are gone, things will be much better for EMS in Peoria.

John

----------

April 18, 2014

Good Friday

Please read

this article from Medscape.

Have a good Easter Sunday.

John

----------

July 10, 2014

Dear Everyone,

This

article was just published in Medscape. Please read the last paragraph first.

Have a great summer.

John

PS: Read this

article too about whistleblowers at the VA. It was published yesterday (July 9, 2014). Here are a few paragraphs about what a VA Emergency Medicine physician in Phoenix thought about her VA facility and what happened to her when she spoke up:

The head of the medical inspector’s office retired June 30 following a report by the Office of Special Counsel saying that his office played down whistleblower complaints pointing to “a troubling pattern of deficient patient care” at VA facilities.

“Intimidation or retaliation — not just against whistleblowers, but against any employee who raises a hand to identify a problem, make a suggestion or report what may be a violation in law, policy or our core values — is absolutely unacceptable,” Gibson said in a statement. “I will not tolerate it in our organization.”

A doctor at the Phoenix veterans hospital, where dozens of veterans died while on waiting lists for appointments, said she was harassed and humiliated after complaining about problems at the hospital.

Dr. Katherine Mitchell said the hospital’s emergency room was severely understaffed and could not keep up with “the dangerous flood of patients” there. Mitchell, a former co-director of the Phoenix VA hospital’s ER, told the House committee that strokes, heart attacks, internal head bleeding and other serious medical problems were missed by staffers “overwhelmed by the glut of patients.”

Her complaints about staffing problems were ignored, Mitchell said, and she was transferred, suspended and reprimanded.

Mitchell, a 16-year veteran at the Phoenix VA, now directs a program for Iraq and Afghanistan veterans at the hospital. She said problems she pointed out to supervisors put patients’ lives at risk.

“It is a bitter irony that our VA cannot guarantee high-quality health care in the middle of cosmopolitan Phoenix” to veterans who survived wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam and Korea, she said.

Scott Davis, a program specialist at the VA’s Health Eligibility Center in Atlanta, said he was placed on involuntary leave after reporting that officials were “wasting millions of dollars” on a direct mail marketing campaign to promote the health care overhaul signed by President Barack Obama. Davis also reported the possible purging and deletion of at least 10,000 veterans’ health records at the Atlanta center. More records and documents could be deleted or manipulated to mask a major backlog and mismanagement, Davis said. Those records would be hard to identify because of computer-system integrity issues, he said.

Rep. Jeff Miller, R-Fla., chairman of the House veterans panel, praised Mitchell and other whistleblowers for coming forward, despite threats of retaliation that included involuntary transfers and suspensions.

“Unlike their supervisors, these whistleblowers have put the interests of veterans before their own,” Miller said. “They understand that metrics and measurements mean nothing without personal responsibility.”

Rather than push whistleblowers out, “it is time that VA embraces their integrity and recommits itself to accomplishing the promise of providing high-quality health care to veterans,” Miller said.

-------------

September 12, 2014

Crowding Kills

-------

January 2, 2016

Hello Everyone,

Article from Medscape on crowding in hospital and emergency room that leads to problems.

In conclusion, EPs should be aware of limitations and risks of providing care for patients in ED hallways. Hospital administrators should be informed that long waiting times, relentless crowding, delays in transferring admitted patients to inpatient areas, as well as ED hallway care, is unacceptable. ED leadership should demand that communication by EPs to hospital administration of unsafe conditions occur without fear of retaliation. Hospital resources must be urgently provided for real solutions to ensure patient safety.

See this article.

Once hospital administrators start getting sued for poor administration, things may change in overcrowded emergency departments.

Harm in the Emergency Department--Ethical Drivers for Change is worth reading also. See the article here. Hospital administrators need to act ethically:

Beneficence is an obligation to assist others in their pursuit of important and legitimate interests. Beneficence includes the identification and removal of possible harms that may deter these pursuits (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2013). Beneficence is most frequently associated with individual actors, i.e. a nurse acting with beneficence while caring for a patient. However, it applies to groups as well. For example, a state government is acting with beneficence when requiring immunizations to prevent the spread of infectious disease throughout the population. Hospital administrators and ED leaders and providers are not acting with beneficence when they allow excessive waiting times as a predictable occurrence in their EDs. Related to beneficence is the corollary of non-maleficence, which is an obligation not to harm others. The evidence informs us that EDs characterized by long waits and high LBBS rates are contributing to institutional harm.

Happy New Year 2016.

-------------------

January 6, 2015--

Crowded hospital EDs not dealing effectively with patient flow

December 28, 2015

Even though most crowded U.S. hospital emergency departments were adopting measures to improve patient flow, they were not adopting the most effective interventions, according to a new study in Health Affairs.

Hospitals “have been slow to adopt interventions that require a change in protocols. This may reflect the fact that ED crowding is a low hospital-wide priority in many facilities, despite the fact that it continues to worsen,” Dr. Leah Honigman Warner, attending physician in the department of emergency medicine at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues wrote in the December 2015 issue of Health Affairs (2015 Dec.;34[12]:2151-2159.

doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0603).

|

©Kimberly Pack/Thinkstock.com

|

Researchers examined data collected from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey on emergency department crowding interventions from 2007 to 2010 and found that “while the average number of crowding interventions adopted by hospitals has increased in recent years, there is still a significant gap in the adoption of many of the strategies that can reduce ED crowding and make crowded EDs safer.”

For example, two interventions – the use of full capacity protocol and boarding in inpatient hallways – were not adopted by the majority of the most crowded quartile of hospitals. Sixty percent of hospitals have not adopted full capacity protocol, and 80% do not transfer admitted patients to wait in inpatient hallways when all beds are full, researchers noted.

To highlight the effectiveness of full capacity protocol, authors point to the Canadian province of Alberta, which adopted the measure and saw ED length-of-stay reduced by one-third and ED boarding reduced by half.

Hospitals during the study period were employing a number of other strategies, including physical space expansion, which has not been proven to help crowding, and technology-related interventions, such as the use of electronic dashboards and computer-assisted triage, both of which are growing and can help reduce length of stay.

“There are data to support the use of ED crowding interventions and proven best practices,” the researchers conclude. “Now is the time for a national campaign to develop the standards to reduce ED crowding and eliminate ED boarding, which will allow hospitals and EDs to provide the highest-quality acute care.”

The authors did not declare any conflicts of interest.

--------

Hi Everyone,

It is March 17, 2016 (St. Patrick's Day). Where does the time go?

Read

this link when you get the chance about long waiting times in the ER.

This is what I was telling OSF 15 years ago.

john

----

Hi Everyone,

Today is January 10, 2018. Where DOES the time go especially when you are having fun?

Read this today in Emergency Medicine News:

I'd also like some help with ED crowding. Multiple studies show crowding is caused by a throughput problem on the inpatient and hospital end, not from a dysfunctional ED. Why not mandate that hospitals, not EDs, put their skin in the game? Reward hospitals that do more with less. Punish hospitals that allow EDs to board patients for days. This would require the hospital to smooth its elective OR schedule (a key reason hospitals are full; cases with “reserved” beds for later) and to come up with creative ways to make the entire hospital more efficient.

Have a great 2018.

john

-----

See above--my letter to Mr. Steffen in September 2001. Today is July 1, 2019.

July 1, 2019

ED Crowding Is Associated with Increased Mortality, Even in Discharged Patients

Daniel M. Lindberg, MD reviewing

Berg LM et al. Ann Emerg Med 2019 Jun 19

Odds of 10-day mortality increased by 50% when EDs were most crowded compared to least crowded.

Emergency department (ED) overcrowding is known to be associated with poor patient outcomes, especially for patients with high acuity or unstable conditions. These authors explored whether crowding is also associated with worse outcomes for more-stable patients.

Using registry data from two large hospital EDs in Sweden from 2009 to 2016, the authors examined 10-day mortality in roughly 706,000 adult patients who were triaged to low acuity levels (scores of 3–5 with the Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System) and discharged to home or to a geriatric care facility. The study included some patients (estimated between 2% and 3%) who left against medical advice or before the visit was complete.

There were 623 deaths within 10 days (0.09%). Factors associated with death were increased length of stay (adjusted odds ratio, 5.86 for mean stay ≥8 hours vs. <2 1.53="" 80="" and="" aor="" be="" comorbidity.="" crowding="" died="" for="" greater="" have="" highest="" hours="" increased="" likely="" lowest="" more="" occupancy-ratio="" older="" p="" patients="" quartile="" relative="" than="" the="" to="" were="" who="" years="">

COMMENT

During periods of crowding, there is a natural impulse to avoid questionable or borderline admissions. Until overcrowding is solved at the hospital and system level, emergency clinicians should take an extra pause before discharging older or more-complex patients during periods of crowding.

-----

A doctor’s warning: Safety is at risk in Ontario’s ERs

By Alan DrummondContributor

Sun., Aug. 11, 2019timer3 min. read

Ontarians have been forced to suffer the indignities of receiving care, if one can call it that, in the ER hallway since the mid-1990s. Hospitals across the province reduced their acute care bed capacity by 30 per cent in an attempt to respond to Paul Martin’s reduction of the national deficit onto the backs of the provinces. It was a matter of balancing the books pure and simple with little to no regard on the effect of patients.

The provinces, in a vain attempt to explain the cuts, promised a healthcare dividend of improved home care and health promotion.

It never happened. Instead, the healthcare needs of an aging population, with their multiple chronic illnesses and co-morbidities, including dementia still needed the hospital ward bed as much as they ever had. As a result, most hospitals far exceed the recognized safe occupancy rate of 85 per cent and in Ontario routinely exceed 100 per cent bed occupancy rates.

Most urban Ontario hospitals routinely have 15-20 per cent of their available acute care beds occupied by the so-called Alternate Level of Care patient; those who no longer need the acute care services of a large hospital but are unable to be discharged because of a family’s inability to cope, insufficient home care and an overall lack of nursing home beds.

Do the math. A 30-per-cent reduction in acute care bed capacity and a further 20-per-cent reduction due to patients with nowhere else to go. The healthcare dividend never materialized and now hospitals and more specifically emergency departments are crowded and dangerous.

For seemingly generations, the Ontario government has tried to paint the problem as one of inappropriate overutilization by patients who would be better served by improved access to primary care. Money has been spent, nay wasted, on attempts at diversion of non-urgent patients away from the ER. All have failed because that never was the problem.

Bed capacity is the issue and under the current government’s plan is not satisfactorily addressed. Yes, we need more nursing home beds but can we afford to wait five or 10 years for these to materialize if ever.

A crowded ER is a dangerous ER. It is not safe. It is a killing ground for your sick and elderly granny and yet governments treat the problem as if it is a mere inconvenience that can wait for system reform that will never come in our lifetime.

These are the facts. A crowded ER, besides exposing your loved ones to incalculable suffering and indignity, leads to an increased risk of medical harm, including death.

An Ontario study of 22 million patient visits to Ontario emergency departments over a five-year period, found that the risk of death and hospital readmission increased incrementally with the degree of crowding at the time the patient arrived in the emergency department. The authors estimated that if the average length of stay in the emergency department was an hour less, about 150 fewer Ontarians would die each year.

Death aside, the crowded ER leads to delayed access to life-saving interventions, infectious outbreaks (remember SARS?) increases the risk of medical error, delirium, the risk of patients leaving without being assessed, hospitalization costs and system gridlock leading to ambulances waiting for interminable hours waiting to offload patients, inability of ambulances to respond to emergencies in the community and an inability to transfer the sick and injured to university hospitals from outlying rural hospitals.

Recently I had a discussion with a seasoned emergency physician at a university hospital in Eastern Ontario who told me the situation was as worse as it had ever been in a long and distinguished career spanning four decades. Eighty patients waiting to be seen in the waiting room, 20 ambulances waiting on the ramp to offload and all the monitored beds occupied, with fully eight patients with cardiac conditions unable to be monitored to a degree acceptable in a western hospital.

The response of the administration? Form several committees to study the problem.

Patients do not know this, but their safety can no longer be guaranteed in an Ontario emergency department.

It is time for the Ford government to do what they promised what they would do in ending hallway medicine. Until such time as the transformation of health care in our province shows some meaningful promise, restore hospital bed capacity to a safe range. Free up some beds; keep Ontarians safe.

Alan Drummond is an emergency physician in Perth and co-chair of public affairs for the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians.

August 6, 2023

Patients Dying in ED Waiting Rooms--August 2023

ED crowding, boarding, systemic failure

JOHN A CARROLL

AUG 6, 2023

My Comments in 2023—

The two articles below hit it on the head. I was saying this in 2001 when I had two elderly patients in the ED who signed out rather than wait in the ED to be admitted.

Unfortunately, ED crowding and ED boarding are still alive and well in 2023.

Patients are Dying in ED Waiting Rooms—Drs. Janke, Tsai, and Panthagani—

But what happens when there aren't any open beds upstairs, on the inpatient side? As most of us have seen all too often, hospitals' preferred fix is to have patients pile up, waiting in the ED until rooms open up. This is what we call "boarding," and it is an ever-present threat to our role in the resuscitative care of the sickest patients. As the mismatch between acute care needs and available capacity mounts, our work environment descends to chaos.

In 2001 at OSF, I thought boarding in the ED was due to a systemic failure within OSF. It was not solely the fault of the ED. I believed it existed where money and patient care intersected and thought that patients were coming out on the short end—like my two elderly patients.

Recently The American College of Emergency Physicians had an article comprised of physician stories about the adverse consequences of boarding—

Multiple physicians shared stories of patients dying in the waiting room because the ED was so overwhelmed, they had to wait for hours to see a physician.

Money seems to be the main driver—

A recent commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine identified "misaligned healthcare economics" as one of the primary drivers of boarding. It is better business for hospitals to keep their medical floors near capacity, prioritize beds for surgical patients who bring in more moneyopens in a new tab or window, and not leave a buffer of open rooms available for predictable surges of ED patients (every Monday afternoon). If more than 90% of beds are full upstairs on Sunday, hospital revenues may be optimized, but dangerous ED gridlock becomes inevitable.

The authors call on HHS to help make improvements in Emergency Departments in the United State to decrease dangerous boarding in the hallways of emergency rooms--

We call on HHS, in cooperation with CMS, to announce a multi-pronged approach to clarifying the problem of ED boarding and identifying solutions. We recommend up-to-date, rapidly-updating, and public reporting from hospitals on waiting room times, boarding times, and rates of patients leaving without being seen. These measures, more so than the simple occupancy measures released to dateopens in a new tab or window, are more often representative of dangerous gridlock. In addition, an anonymized reporting mechanism should be created for healthcare providers to share their staffing ratios. This commission should prepare a report for Congress including detailed data on ED boarding as well as stories from healthcare workers on the tragedies they've seen. Transparency on the state of hospital preparedness is an essential first step.

Patients Are Dying in Emergency Department Waiting Rooms

— We call on HHS and CMS to help address the issue of ED boarding

by Alexander T. Janke, MD, MHS, Jennifer Tsai, MD, Med, and Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD February 19, 2023

A photo of a crowded hospital hallway.

A special session of Congress was called 35 years ago to make lawmakers and the public aware of stories of patients left to die in hospital parking lots for lack of insurance. Around the time of that congressional testimony, called "Equal Access to Health Care: Patient Dumping," a new guarantee came about: that any individual who comes to the emergency department (ED) must be givenopens in a new tab or window a medical screening evaluation and appropriate stabilization. This codifies the ED, by federal lawopens in a new tab or window, as the front door to hospital-based care in the U.S.

In its ideal form, the ED is well-calibrated for the rapid identification of life- and limb-threatening acute illness and injury. For the vast majority of patients, no such dangerous pathology is present, and for a small subset of the sickest patients, our core mission is resuscitative care. After that, we act as a flexible acute diagnostic and therapeutic center that ends in disposition: discharge or hospital admission.

But what happens when there aren't any open beds upstairs, on the inpatient side? As most of us have seen all too often, hospitals' preferred fix is to have patients pile up, waiting in the ED until rooms open up. This is what we call "boarding," and it is an ever-present threat to our role in the resuscitative care of the sickest patients. As the mismatch between acute care needs and available capacity mounts, our work environment descends to chaos.

Patients are now waiting hours, days, and sometimes weeks in the ED. It's like asking a teacher to take on a whole new class of students when last year's class hasn't left yet.

New data from two studiesopens in a new tab or window we recently published in JAMA Network Open document what patients, nurses, and doctors already know: the levees have broken. The system has collapsed under the weight of acute care needs.

At the end of 2021, in the hardest-hit hospitals, more than one in 10 ED patients left without careopens in a new tab or window. Half of the sickest patients in the department -- those requiring admission -- waited 9 or more hoursopens in a new tab or window for an inpatient bed. More and more, patients are placed in hallways: patients who need sensitive exams, patients with highly infectious respiratory viruses, and elderly patients with sepsis who must endure the bright hall lights through the night.

The problem isn't just physical space -- it's staff. Nurses, crushed under the weight of a profit-driven staffing crisis years in the makingopens in a new tab or window, must now care for both admitted boarding patients and new patients. In practice, there are often no limits on staffing ratios for ED nurses. On the medical floor, a single nurse may have four to five patients. In the ICU, two patients. In the ED, a single nurse is often asked to cover 10 patients or more, some critically ill who are "admitted" but in the ED waiting for an ICU bed, without regard for the safety or sustainability of this arrangement.

A recent surveyopens in a new tab or window by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) invited ED doctors to share what they've seen happen as a result of ED boarding. Patients with brain bleeds, hip fractures, and even necrotizing genital infections are being treated in the waiting room because there are no rooms or even hallway beds available in the ED.

Multiple physicians shared stories of patients dying in the waiting room because the ED was so overwhelmed, they had to wait for hours to see a physician.

Why Aren't Hospitals Ready for Patients?

ED boarding is not simply a matter of too many ED patients or inefficient ED staff. Staffing shortages throughout the hospital, reduced capacity at nursing facilities, and "business hours" scheduling of inpatient specialized services all lead to inefficient patient flow through the hospital, ultimately causing a backup in the ED.

But perhaps the most significant roadblock to solving ED boarding is that hospitals are financially disincentivized from fixing it.

A recent commentaryopens in a new tab or window in the New England Journal of Medicine identified "misaligned healthcare economics" as one of the primary drivers of boarding. It is better business for hospitals to keep their medical floors near capacity, prioritize beds for surgical patients who bring in more moneyopens in a new tab or window, and not leave a buffer of open rooms available for predictable surges of ED patients (every Monday afternoon). If more than 90% of beds are full upstairs on Sunday, hospital revenues may be optimized, but dangerous ED gridlock becomes inevitable.

Despite decades of academic work demonstrating the dangersopens in a new tab or window, the only standard set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) on ED boarding is a recommended 4-hour maximum boarding time (we're way past that on a good day), with no mandatory reporting requirements. In 2016, CMS introduced a second metric: an option for hospitals to report boarding times as a part of their quality measures. In 2021, when CMS saw hospitals who voluntarily reported boarding times were not reaching crisis levels, they discontinued the metricopens in a new tab or window, concluding ED boarding was not an issue. Of course, it's highly likely that when hospitals did reach crisis levels, they simply chose not to report that data.

We call on HHS, in cooperation with CMS, to announce a multi-pronged approach to clarifying the problem of ED boarding and identifying solutions. We recommend up-to-date, rapidly-updating, and public reporting from hospitals on waiting room times, boarding times, and rates of patients leaving without being seen. These measures, more so than the simple occupancy measures released to dateopens in a new tab or window, are more often representative of dangerous gridlock. In addition, an anonymized reporting mechanism should be created for healthcare providers to share their staffing ratios. This commission should prepare a report for Congress including detailed data on ED boarding as well as stories from healthcare workers on the tragedies they've seen. Transparency on the state of hospital preparedness is an essential first step. In combination with the right regulatory mechanismsopens in a new tab or window and financial incentives, we can incentivize the availability of flexible capacity and cooperation among disparate health services organizations to relieve dangerous conditions during times of surge demand for acute care.

The crisis is ongoing. Will policymakers and health system leaders take note?

Alexander T. Janke, MD, MHS,opens in a new tab or window is a fellow in the National Clinician Scholars Program at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation. Jennifer Tsai, MD, MEd,opens in a new tab or window is an emergency medicine resident physician at Yale School of Medicine. Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD,opens in a new tab or window is an emergency resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar at Yale School of Medicine.

Many comments were posted and here is a fragment of one comment by Toni_Kingo—

Economists are running hospitals instead of doctors. Their decisions are oftenly geared towards the interests of the owners and they see the ED department as a sink hole when poor people are concerned. In more than one occasions have we seen instructions being given or passed on by osmosis to the ED that there is no space in the various sections of the hospital while they simply hope for the patient to die.

This emergency within the emergency is left to remain like that for years on years. So thereby it stops being an emergency and begins to be daily routine, just as it was planned by the hospital economist. Cast your net and catch.

An emergency in U.S. emergency care: Two studies show rising strain

Institute for Health Care Policy and Innovation—University of Michigan

https://ihpi.umich.edu/news/emergency-us-emergency-care-two-studies-show-rising-strain

October 7, 2022

Full hospitals and staffing shortages combine to leave patients waiting hours for beds or leaving without being seen by a physician at all—

Despite decades of effort to change emergency care at American hospitals and cope with ever-growing numbers of patient visits, the system is showing increasing signs of severe strain, according to two new studies.

The work has implications for health policy, providing data that shows the key role of the availability of staffed hospital beds in the ability of emergency departments to serve patients, whether or not COVID-19 cases are surging.

The studies, based on electronic health record data from across the country, are published in JAMA Network Open by a team from the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, and Yale University.

Alex Janke, M.D., M.H.S., the lead author of both studies, is a National Clinician Scholar at the VAAHS and IHPI who currently provides emergency care at the VAAHS and at Hurley Hospital in Flint, Mich. He notes that the studies are a limited window into an enormous problem, and better data will be essential to guiding government entities, insurers and health systems into sustainable improvements.

“Emergency departments are the levees on acute care demands in the U.S.,” says Janke, who trained at Yale before coming to Michigan. “While once there were decompression periods in even the busiest EDs, what we are seeing here, as others are seeing in Canada and the U.K., demonstrates that the levees have broken.”

In one study, the researchers examined the percentage of emergency department patients who left without being seen by a physician – likely due to long wait times in crowded conditions.

The median percentage across all hospitals in the study doubled from 2017 to the end of 2021, from just over 1% to just over 2%.

But then the researchers dove deeper into data from the 1,769 hospitals in the study sample at the end of 2021, dividing them up by percentage of patients who left without being seen.

A full 5% of hospitals had more than 10% of the patients who entered their emergency departments leave before they could have a medical evaluation. That’s more than double what it was in the same tier of hospitals in 2017 and the early part of 2020.

In the second study, the researchers calculated the number of hours that emergency department patients who required hospitalization had to wait, or “board”, in the ED before they actually got a hospital bed.

They looked at how the overall occupancy of each hospital at the time of boarding was associated with how long patients had to wait in the ED for a bed.

The national accrediting body for hospitals recommends that boarding times be kept below four hours, to prevent delays in care and known safety issues.

But the study shows that when hospitals had more than 85% of their staffed beds already occupied by other patients, admitted patients in emergency departments had to wait for their bed more than four hours nearly 90% of the time. In fact, such patients found themselves waiting on average more than 6.5 hours for a bed, compared with 2.4 hours during times when hospitals were less full.

By the end of 2021, the median boarding times nationally were approaching the maximum recommended time, at 3.4 hours. At the 5% of hospitals with the highest occupancy, median boarding times were more than nine hours.

Nationally, the percentage of hospital beds occupied at any given time didn’t change much from 2020 to 2021. But the number of emergency visits grew, and boarding times worsened.

The researchers note that their data source doesn’t allow them to dive into what factors made hospitals more likely to have high occupancy, long boarding times or high percentages of emergency department patients leaving before they could be seen.

They do note, however, that the strain isn’t evenly distributed across hospitals that have emergency departments.

“Boarding and overcrowding in EDs have been a growing issue for over 30 years. Incredible work has been done in the emergency medicine community to make our care better, more accurate and nimbler using limited resources,” says Janke. “But without more space and staff in the hospital, and downstream in skilled nursing facilities and across community settings, this crisis will continue.”

In addition to Janke, the study’s authors are Yale’s Edward R. Melnick, MD, MHS and Arjun K. Venkatesh, MD, MBA, MHS. “This is not an ED management issue,” said Venkatesh, an associate professor of emergency medicine at Yale School of Medicine. “These are indicators of overwhelmed resources and symptoms of deeper problems in the health care system.”

The study was funded by Janke's support from the Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and the University of Michigan, and by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Foundation

Hospital Occupancy and Emergency Department Boarding During the COVID-19 Pandemic, JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(9):e2233964. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33964

Monthly Rates of Patients Who Left Before Accessing Care in US Emergency Departments, 2017-2021, JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233708. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33708

—

John A. Carroll, MD

www.haitianhearts.org

COMMENT